Option 3 Conclusion : Mandate Now rejects the proposal.

The proposal requires no one to report anything because there is no legal mandate to report. No one is protected if they do report a concern because the report remains discretionary since the required action under the duty is unspecified. If they don’t act in a way they should have acted, and with the benefit of hindsight and possibly years later, the failure to act ‘could’ be criminalised.

The proposal is designed to achieve nothing; it is an exercise in afterthought that contributes nothing to the long-needed change to the culture in child protection.

- It is after the event child abuse legislation that might scapegoat the odd person.

- It cannot positively impact the culture of child protection.

- The action to be taken is unspecified which leaves staff unprotected if they decide to take action.

- It is a duty to take unspecified “appropriate action” which varies according to circumstance. It would be an extremely challenging offence to prove. Nothing so vague could have a criminal sanction attached.

- In less serious cases it is proposed that the duty to act will be enforced by disciplinary sanctions rather than criminal sanctions. This depends on organisations acting potentially against their own interests to apply disciplinary sanctions. There is no proposed sanction on an organisation for failing to take disciplinary action.

- The cases where the proposal anticipates criminal sanctions will be used are narrow and require such a degree of knowledge of the abuse by the accused as to be almost impossible to prove. No prosecutions will occur

- Having an unspecified duty to act is an open invitation to some RAs to handle abuse cases “in house”, rather than report to the LADO in the case of schools or the the Local Authority MASH. They will claim that they were acting reasonably and in good faith, and it will be in almost all cases be impossible to prove otherwise.

Observations on Content and design of the Consultation

The Consultee proposes one of two options featured in the consultation to be applied to those gathered under the newly created definition ‘Practitioner.’

Unfortunately the proposition that one of two options can fit all ‘practitioners’ is flawed. The options proposed fail each of the distinct and different roles they seek to include.

The introduction of the term ‘Practitioner’

The term has been created specifically for the consultation. It permits the consultee to assemble many disparate child protection roles under one definition for no good reason. It serves to confuse. Perhaps it is driven by a wish to achieve a ‘one initiative fits all’ proposition that will ‘fail each.’ We detail why in the our reviews of the proposals.

It is known and understood that social workers are against the principle of MR for familial settings. We agree, which is why our proposal, to be posted in ‘News’ on this site shortly, only address mandatory reporting in Regulated Activities (‘RAs’). Social workers have nothing to do with either the creation of child protection policies or their delivery in RAs. The terms of reference for the The Munro Review of Child Protection for example, excluded this very different and specific area of child protection.

The consultation definition of ‘practitioner’ lists the following roles.

- Director of Children’s Services – The recipients of referrals. MR law therefore inappropriate

- Social Workers – employed by the LA who receive and deal with referrals

- Housing Officers

- Police Officers / Community Support Officers / Civilian Police staff. (An agency that deals referrals)

- Probation Officers.

With the exception of Housing and Probation Officers (All these are listed in Section A2, P5 of Impact Assessment) all are agencies that receive allegations from RAs (and elsewhere), and provide appropriate responses. An entirely different role to those performed by RAs.

A number of Child Sexual Exploitation cases have highlighted a lack of response and accountability in referral receiving roles, Rotherham to highlight one. Option 3, ‘Duty to Act,’ which is a variation of wilful neglect suggested by David Cameron in the House Of Commons following the release of the Serious Case Review into the Oxford Child Sexual Exploitation case 3/3/2015, is after the event legislation that will make no difference to the culture of child protection at the Local Authority. We provide an explanation in our review.

Meanwhile we have already reviewed Option 2 which is inappropriate for non-Regulated Activities. Its design fails to deliver mandatory reporting as we explain in our review available here.

___________

Assessment of Option 3 – ‘Duty to Act’

The problem with the duty to act is clear from the first paragraph of the description (paragraph 53).

“The introduction of a duty to act would impose a legal requirement on certain groups, professionals or organisations to take appropriate action where they know or suspect that a child is suffering, or is at risk of suffering, abuse or neglect.”

The problem is compounded with the clarification in the next paragraph (para 54).

“Making decisions about what action to take in response to abuse and neglect is not always straightforward. What would be considered to be appropriate action under the duty to act would therefore depend on the particular circumstances of each case.”

In essence, an unspecified “appropriate action” which will vary between individual cases is being defined as a legal duty possibly subject to prosecution and criminal sanctions for failure. A more unworkable basis for a law is hard to imagine.

It is stated in paragraph 54 that:

“Practitioners working with children would be responsible, as they are now, for considering what action is needed to protect them from harm and acting accordingly.”

And it is claimed that:

“The duty to act would make practitioners more accountable for such decisions.”

Quite apart from the tautology involved since practitioners are defined as being those working with children, this quite frankly is nonsense. Unless the duty is made specific, then accountability is absent because there will almost always be ways of arguing that a person was acting reasonably in good faith.

If improved outcomes in terms of protecting children are going to be achieved, what is needed above all is clarity in what responsible the adults are expected to do when suspecting harm. Such a nebulous “duty to act” provides the opposite of clarity.

The description of grounds for prosecution in paragraph 57 makes it even more clear how unworkable this proposal would be in practice.

“This means that an individual would have to consciously take a decision not to take action, or take action which was clearly insufficient or inappropriate, in the knowledge that they were not doing the right thing or reckless as to whether they were.”

That degree of knowledge is going to be almost impossible to demonstrate, and so prosecutions are going to be rare bordering on non-existent.

Paragraph 58 does allow that a person could fail to act in a way less culpable.

“In many cases, failures to take appropriate action to protect children will not be deliberate or reckless in nature. Sometimes the reasons might relate to failures of professional practice or because of organisational dysfunction. In cases like these, existing sanctions available to employers or regulators would continue to be available. The introduction of a new statutory duty to act might increase the use of such sanctions by employers and/or regulators.”

This shows what appears on the face of it to be a complete misunderstanding of what a law can do. A law cannot oblige an organisation to take disciplinary measures against a person for a failure which the state itself is unable or unwilling to punish. Part of the problem of child sexual abuse within organisations is that the reputation of the organisation is too often put ahead of the welfare of the children in the organisation’s care, and that those who try to report or take other appropriate action to protect children are currently whistleblowers and all-too-frequently sacked or otherwise disciplined. Relying on organisations to police an unspecified duty to act is giving a new name to the status quo, where there is in fact no specific duty to report abuse. Moreover, expecting organisations to act this way against their own interests is quite clearly futile.

A vital aspect of improving outcomes is maximising the number of abuse cases that reach the attention of those trained to assess the situation properly and who have the power and authority to intervene effectively. Recent figures produced by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England suggest that only 1 in 8 victims of child sexual abuse actually comes to the attention of the authorities[19] . An unspecified duty to act is an open invitation for organisations to fulfil that “duty” by investigating and handling allegations of abuse in-house without contacting the authorities and having to deal with the consequent bad publicity. Of course the Government may see this as useful in order to keep referrals to the LA artificially low.

Such an approach by organisations might not necessarily be maliciously intended. They might quite genuinely believe that they are acting in such a way as to both protect the children in their care and the reputation and operation of the organisation. In practice, the only person they are protecting is the abuser. Once an abuser finds that he is not being reported the first time he is caught, he will realise that he can abuse again with impunity. Moreover, any other potential abusers working for the organisation will also realise their chances of being caught and prosecuted are minimal. The organisation having failed to report the first incident will be on the horns of a terrible dilemma if another incident occurs with either the same or a different abuser. If they now report the second incident, they can hardly prevent their earlier bad decision from coming to light, and the reputational damage to the organisation will be much greater. Hillside First School in Weston-Super-Mare had precisely this shortcoming[20]. The temptation will be to find a way of continuing not to report while making what the organisation genuinely believes are valid good faith attempts to protect the children in its care. And so over years or decades of non-reporting an organisation becomes a honey-pot to abusers who are confident they will not be reported or prosecuted. This is why when a case of institutional abuse comes to light, it often transpires that several abusers have been active in the same place by the time the abuse is finally uncovered.

A classic example of this came to light a few years ago. Richard White (also known as Father Nicholas White) was a monk at Downside Abbey and a teacher at Downside School, an independent Roman Catholic boarding school run by the monks of the abbey. He was caught sexually abusing a pupil. Rather than report the matter, they continued to allow White to teach, but barred him from contact with the youngest boys. He abused again the following year, and again rather than report the matter the abbey sent White to another monastery, Fort Augustus Abbey in Scotland, where White remained for several years before returning to Downside when Fort Augustus closed.

The abbey and school took advice from their solicitors about whether they had a legal obligation to report, and were advised (quite correctly in law) that no obligation existed. The police stumbled across the case some years later going through school records in the course of another unrelated investigation. White was sentenced to 5 years. Nobody in the school was prosecuted for failure to report as no law had been broken. Soon after, it emerged that seven or eight abusers had been active at the school over a period of decades, though not all of them at the same time.

Since the ‘duty to act’ is so unspecific in the action required, it is likely that the same course of events would occur under a duty to act law. If the duty does not necessarily include reporting incidents or suspicions to the authorities, then an organisation could act as described above and could claim that they were acting in good faith in protecting the children in their care. A prosecution would be most unlikely since an action was actually taken to protect children, and they would argue that they were not to know that it would turn out to be inadequate.

Paragraph 59 described the “possible benefits” of a duty to act law. The first one is to “strengthen the existing mechanisms for ensuring accountability arrangements in the child protection system”. A prerequisite of accountability is that there is clarity in the action required, so people know exactly what is expected of them. The duty to act proposal is so unclear that no improvement in accountability can possibly be achieved.

The second “possible benefit” is to “aim to increase awareness of the importance of taking action in relation to child abuse and neglect, both by those under a duty to act and the general public”. There is no reason to think there is any lack of understanding in principle of the need to act. The problem is turning principle into practice, in that people are not clear about what action is expected of them in specific circumstances they might reasonably expect to encounter when at work, and are fearful of the consequences of raising a false alarm even in good faith. The lack of clarity in the duty to act proposal will do absolutely nothing to remedy this. Please refer to footnote 4 on page 2 the comments of Chris Husbands, Director of the Institute of Education at the time.

The third possible benefit is to “change the behaviour of those covered by the duty by putting in place a clear requirement to take action in relation to child abuse and neglect.” The duty will obviously fail in this aim because it simply doesn’t provide the “clear requirement to take action” on which the change in behaviour is predicated.

The benefits are so obviously illusory that it almost seems unnecessary to look at the stated possible risks and issues in paragraph 60, but there are in fact some very serious misapprehensions there as well.

The first risk is that there could be “an increase in unnecessary state intrusion into family life by increasing inappropriate activity throughout the system. In some circumstances this might make it harder to distinguish real cases of abuse and neglect. Appropriate action may not be taken in every case as a result”. If the standard of success is that appropriate action is taken in every case then almost any initiative can be condemned as inappropriate. It is a damning reflection on the authors of this document that in a situation where an estimated 7 out of 8 abused children never come to the attention of the authorities, their first concern is false alarms. This concern can always be used as a justification for doing nothing.

Any action that might lead to more cases coming to light is likely to involve at least some more false alarms. It is as if the author is looking to address a newly-discovered major fire hazard primarily by devising measures to reduce the number of false alarms lest the fire service are unable to respond as fast as they might in the event that a fire actually starts. In fact, what is needed is first to take measures to address the hazard itself in order to prevent a fire from starting and spreading.

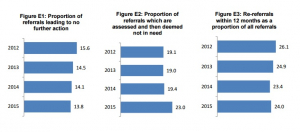

Even now, according to Figure E.1 (SFR) document 22 October 2015³ titled “Characteristics of children in need: 2014 to 2015³”, for the year of 2015: 13.8% of referrals lead to no action and a further 23% were assessed and the child deemed as “not in need” (over a third in total).

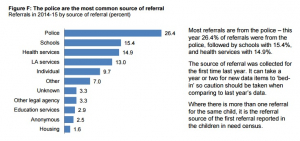

The great majority of referrals are from groups Mandate Now proposes should be included in the mandatory reporting requirement: the police, schools, health services and LA services between them account for 70% (see Figure G ) of all referrals.

Although these groups originate the great majority of referrals, we know from investigations into failings of the system that very many more cases could and should be reported from these sources and that that Mathews et al study in Western Australia suggests that numbers of reports from these groups can be tripled with no loss of quality.

In the context of child protection, the only way to avoid any false alarms is effectively to dismantle all child protection services so there are no resources to discover that any false alarms have occurred. Unfortunately this means that instead of merely 7 out of every 8 abused children not coming to the attention of the authorities, we would bring the figure up to 8 out of 8.

The second possible risk is this action would “lead to those bound by the duty feeling less able to discuss cases openly for fear of sanctions, hindering recruitment and leading to experienced, capable staff leaving their positions”. This happens already. The best that can be said is that a duty to act requirement as vaguely stated as is described here would make not one whit of difference to the situation.

The third possible risk is to “allow scope for those bound by the duty to make incorrect judgements about what action is appropriate in some cases”. Perfectly true, and if anything somewhat understated given how uselessly vague the duty is.

The last possible risk is that the new duty to act would “have limited benefits for further raising awareness of the importance of taking action in relation to child abuse and neglect given the new Government communications activity, the existing high level of media scrutiny and the work of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse”. The statement that about “limited benefits for further raising awareness” is true, but the reasons for it go far deeper than new government communications and the work of the IICSA. The limited benefits simply result from a vague, comprehensively flawed and muddled concept.

The comparison between duty to act and mandatory reporting in paragraph 61 introduces a false dichotomy, as if we could introduce one measure or the other but not both. The problem with the duty to report proposal as stated is its vagueness. The mandatory reporting option (as proposed by Mandate Now if not as described in the consultation document) has the admirable benefit of clarity. In the specific circumstance in which a mandatory reporting duty applies, it is crystal clear what is expected of people. Only that clarity can affect behaviour.

It is accepted that mandatory reporting is not a magic bullet that will cure all the failings of the child protection system. It is designed to deal with one specific but critical issue, in ensuring that more reasonably grounded suspicions of abuse come to the attention of those with the training and authority to respond effectively and to protect those who act to achieve this. With the present system missing an estimated 7 out of 8 abused children, it is clear that urgent action is needed on this point.

The duty to act proposal is trying to be that magic bullet, by making a duty in law to act in some unspecified but appropriate fashion at all points in the child protection system. The aim is laudable but the method proposed is useless and doomed to failure. If it were so simple it could have been done years ago and there would not be any need for the IICSA to be investigating decades of failure. And where in the world is such a system operating? Where is the evidence of its effectiveness?

The failure to bring many children to the attention of the authorities so that they can be better protected is obviously not the only weakness in the system. Other weaknesses will have to be targeted by other specific and clearly defined measures. Where the individual weaknesses occur and what are the appropriate measures to address them is outside the scope of this consultation. The introduction of mandatory reporting does not obviate the need to identify and rectify those other weaknesses. In fact mandatory reporting, by bringing more cases to light, may cause other weaknesses to become more obvious if the largest remaining failure point in the system is now elsewhere.

No analysis is made here of the proposals in part D concerning to whom the duty would apply to and when it would apply. The proposals here are very similar to the proposals for mandatory reporting and are analysed elsewhere. Since the duty to act is essentially meaningless and unenforceable, it doesn’t much matter who it applies to or when, since it will have no effect whatever choices are made in these matters.

However the proposals concerning sanctions (para 71-74) are worthy of separate comment. The suggestion in para 72 is that “Sanctions for breach of either of the new statutory measures could be subject to the existing practitioner and organisation specific sanctions”. In other words we are talking of disciplinary sanctions rather than criminal sanctions. Such disciplinary sanctions already exist, but depend for the effectiveness on public and private institutions being prepared to apply them. The problem is that in too many cases the institutions are either too disorganised to apply sanctions effectively, or will choose not to apply sanctions where it perceives the resulting publicity may be adverse. The possibility also needs to be considered that with such a vague “duty” disciplinary sanctions may be misused for reasons of internal organisational politics.

Furthermore, if the sanctions are merely disciplinary rather than criminal, the duty to act is not a statutory legal duty. It is a behavioural expectation dressed up in legal language and having no force. It is a maintenance of the existing unacceptable status quo. Let nobody be misled on this point. This kind of pseudo-legal sleight of hand is visible in successive editions of the documents ‘Working together to protect children’ and “Keeping children safe in education’ which have been labelled “statutory guidance” even though they contain almost nothing that has any legal force. Continuing with more of the same sort of thing is certain to achieve the same unsatisfactory outcomes.

Paragraph 73 proposes additional processes involving the disclosure and barring service. However regulations already exist requiring organisations to notify DBS (or its predecessor organisations) and to the best of our knowledge no organisation has ever been prosecuted or otherwise sanctioned for failing to make a notification to the DBS despite it being a legal requirement. In any case, what is being described here is not a sanction, but in fact a new duty to make DBS notifications of ‘practitioners’ who fail to act. Since the existing arrangements for notifying DBS of people who have abused or are suspected of abuse are as full of holes as a colander, extending it to cover people who have merely failed to act looks like window dressing with no possible practical effect.

Paragraph 74 does mention possible criminal sanctions, but as described above within the context of the duty to act, the circumstances necessary to prosecute and apply a criminal sanction are impossible to achieve in practice. The range of sanctions for such an impossible case therefore becomes irrelevant and merely hypothetical.