Conclusion : Mandate Now rejects the Government’s option 2 proposal in the consultation which was issued on 21/7/16

- Through the definition of the term “practitioner” LA children’s services will both be mandated reporters and the recipients of their own reports.

- The proposal allows no flexibility in LA arrangements for triaging and handling reports for instance using the LADO or a Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub.

- Less serious cases of non-reporting will be addressed by disciplinary rather than criminal sanctions. Such sanctions have failed to influence child protection. Sanctions depend on organisations acting potentially against their own interests to apply disciplinary sanctions. There is no proposed sanction on an organisation for failing to take disciplinary action, therefore this is not “mandatory” reporting but a minor variation to the discretionary reporting arrangements currently in

- The consultation proposal provides little or nothing in the way of legal protections for those who report.

- The proposal covers only a limited number of Regulated Activities

There are three curious things about the consultation proposal for mandatory reporting.

The first is the brevity of the description, about two pages out of a consultation document of 36 pages (excluding another 45 pages of annexes).

The second is how negative the language is that is used to describe mandatory reporting. From reading the proposal one could think the Home Office wants to solicit arguments against mandatory reporting and for what appears to be its favoured and flawed option of “duty to act ”.

The third is how little the MR proposal resembles the draft amendment on mandatory reporting in amendment 43 tabled by Baroness Walmsley (LD) , in the Serious Crimes Bill and withdrawn in exchange for the promise of this consultation.

The description starts badly, in paragraph 45.

“Mandatory reporting is a legal requirement imposed on certain groups, practitioners or organisations to report child abuse and neglect. If such a duty were to be introduced in England, reports would be made to local authority children’s social care.”

The first problem is the words “report child abuse”. That requires fairly certain knowledge of abuse to exist in the mind of the reporter. In practice it rarely exists, especially in cases of child sexual abuse, where the initial evidence is often equivocal.

What needs to be reported is a reasonable suspicion of child abuse or neglect, i.e. not something that by itself would justify prosecution, but might be the starting point for an investigation.

The second problem is the use of the word “practitioners”. We detailed our misgivings about this newly created term earlier in this submission. “Practitioners” is defined (in a consultation footnote) as follows.

“The term ‘practitioners’ is used throughout the consultation to refer to individuals who work with children in any capacity.”

Note: any capacity. By the consultation’s own definition of mandatory reporting, that would require those working with children in local authority children’s social care both to be mandatory reporters and the recipients of their own reports. This is clearly nonsense. Moreover, it is likely to be interpreted by the social work profession as yet another unreasonable demand being made on a stretched profession, so as to give politicians an easy target for when (as inevitably happens from time to time) a child is harmed who might have been protected.

So let’s be clear, a reasonable mandatory reporting regime will have local authority children’s social care as the ultimate recipients of reports, rather than as mandated originators. Local authority children’s social care already has a statutory duty to investigate child protection concerns that are brought to its attention, and there is no reason for mandatory reporting to change anything about that.

And there is a third problem, that it is assumed that local authority children’s social care will be the recipients of the reports. While they will be the ultimate recipients, many local authorities have defined a single point of contact for a variety of reports (sometimes called a Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub) where reports are triaged and then passed to the most appropriate agency. The definition in the consultation does not appear to allow for this kind of flexibility in where reports by mandated reporters should be sent. Triage of reports is a vitally important and necessary function.

It is important that mandatory reporting is not discarded simply because the description of it in this consultation paper is poorly thought-out.

Paragraph 46 is simply a statement of fact that there are different mandatory reporting arrangements in place in different countries, and that different proposals exist for how mandatory reporting should be introduced here.

Paragraph 47 describes the range of possible sanctions. The proposal states that “These could range from employer and/or regulatory sanctions to criminal sanctions”.

If we are talking of “employer and/or regulatory sanctions” then it quite simply is not mandatory reporting. We already have employer and regulatory sanctions, they are rarely applied (in fact they seem sometimes to be applied more often to whistleblowers who do report than to those who fail to report). So employer and/or regulatory sanctions is actually the existing system of discretionary reporting that we have now. It is the status quo with new words to describe it.

Therefore, if we are talking about effective mandatory reporting there needs to be a criminal sanction. Talk of anything else can serve only to sow confusion. With so many shortcomings in just three paragraphs the proposal is either the product of a frightening degree of ignorance of the subject or is designed to be rejected.

We then get to paragraph 49, which is actually a reasonable (if brief) description of the possible benefits of a mandatory reporting system. It’s worth looking at each point in turn.

“…increase awareness of the importance of reporting child abuse and neglect, both by those under a duty to report and the general public;”

Perfectly true, though it is a bit odd to start with this somewhat indirect and intangible benefit.

“…lead to more cases of child abuse and neglect being identified, and at an earlier point in a child’s life than is currently the case;”

Also perfectly true. We have previously referred to the latest and very specific research on the introduction of mandatory reporting in Western Australia by Professor Ben Mathews.[1]

“…create a higher risk environment for abusers or potential abusers because the number of reports being made would be likely to increase;”

This is another indirect but probable effect. If mandatory reporting brings about a culture of vigilance in institutions such as schools, then the abusers who are most prolific because they work their way into a position of trust within an institution may be deterred from trying to abuse. In certain ways child abusers are much like other criminals, in that they don’t want to get caught and will avoid taking unreasonable risks of being caught.

“…ensure that those best placed to make judgements about whether abuse and/or neglect is happening – social workers – do so. Practitioners (i.e. those who work with children in any capacity) have not always been able to confidently conclude when a child is being abused or neglected or is at risk of abuse or neglect. Requiring a wide range of practitioners (see part D) to report would enable these difficult cases to be examined by social workers.”

This is actually the most important and direct benefit of mandatory reporting, and should have been placed first. We need these reports to be in the hands of those equipped to evaluate them. We propose the LADO for very clear reasons. Teachers for instance are primarily trained to teach. They are not trained to investigate or evaluate cases of children at risk of abuse.

The present discretionary system provides far too many brakes on reporting. Evidence (particularly of sexual abuse) is often not very clear cut, and could consist of something as vague as age-inappropriate sexual knowledge or behaviour which might indicate abuse or might possibly have a more innocent explanation.

A suspicion /allegation of abuse is such a horrible thing that a person will very naturally wonder “what if I’m wrong?” and think of all the adverse consequences, from accusing an innocent person, wrecking somebody’s career, being themselves accused of making a malicious accusation, being labelled a troublemaker or whistleblower possibly against a trusted colleague.

The general public assume that anybody would instantly report abuse if they saw it. However the general public are rarely faced with circumstances in which that assumption gets tested. Moving from the general belief that one would always report to the specific case of actually having to do so is a far greater step than many realise. What if you’re wrong?

At present, the consequences to the reporter for failing to report are relatively small, and so the question “What if I’m right?” gets somewhat less of an airing.

The main effect of a well-implemented mandatory reporting scheme is to create an environment which protects those who would report but currently have fears about doing so. They will know precisely what is expected of them, and know that sanctions can hardly be brought against them for performing their legal obligation. The “what if I’m wrong” question loses much of its worry.

Paragraph 50 lists what the author believes to be the “possible risks and issues”. There were only four items in the list of positives, the author has included no fewer than eight negatives. The author believes mandatory reporting could:

“…result in an increase in unsubstantiated referrals. Unsubstantiated referrals may unnecessarily increase state intrusion into family life and make it harder to distinguish real cases of abuse and neglect. Appropriate action may not be taken in every case as a result”

If there is an increase in total referrals then there is almost certain to be an increase in the absolute number of cases that are unsubstantiated. The research by Mathews[2] referred to above suggests reports from mandated reporters more than triple, and the substantiation rate remained roughly constant.

The statement however appears to be implying without quite openly saying that the proportion of unsubstantiated referrals will rise, and that children’s services will be swamped with a flood of trivial referrals. It is true that an exceedingly badly designed mandatory reporting system might have that effect, by defining an extremely low threshold for a suspicion of abuse and an extremely onerous sanction, such as imprisonment, for failure to report. But there is no reason to design mandatory reporting in such a foolish way.

But even if the proportion of unsubstantiated cases does rise, this is not necessarily a bad thing. In his paper Mathews makes the point that substantiation rates are not all that useful a measure of effectiveness. Other research has already discovered that “Many reports of abuse and neglect that are investigated but unsubstantiated do involve abuse and provide opportunities for early intervention” and as a result have concluded that substantiation is “a distinction without a difference[3]” and that it is “time to leave substantiation behind[4] and that “substantiation is a flawed measure of child maltreatment. . .policy and practice related to substantiation are due for a fresh appraisal[5]”. For instance, a report of suspected CSA is frequently based on the reporter observing the child’s adverse health symptomatology, behaviour, and social context. In such circumstances, there is often a health and welfare need whether or not the CSA is substantiated. Mathews also points out that substantiation rates can also be markedly affected by such things as policy variations in setting evidentiary thresholds, the capacity of agencies to investigate, and whether there is an emphasis on evaluating existing harm or assessing the risk of future harm.

Mathews: “there is not firm ground for concluding that when exploring trends in reporting and report outcomes, the sole measure of the soundness of a report of suspected CSA is whether it is substantiated. Outcomes such as actual service provision to the child, and perceived need for service provision even if this is unable to be provided, are among those that are also relevant.”

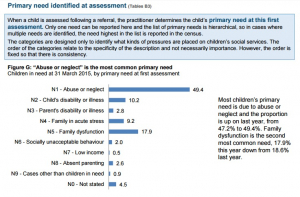

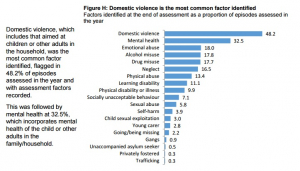

Mathews’ conclusion is supported by the Government’s (SFR) document “Characteristics of children in need: ”22 October 2015³. Figure G indicates that almost half (49.4%) of

referrals are for “abuse or neglect” but Figure H indicates that the most common factor identified at the end of assessment is domestic violence at 48.2% with emotional abuse at 18%, neglect 16.5%, physical abuse 13.4% and sexual abuse 5.8%.

The figures aren’t directly comparable because more than one factor can be identified at the end of assessment so the categories in Figure H add up to more than 100%. Even so, it appears that abuse or neglect is sometimes not a factor identified at the end of the assessment even though that is what was referred. However, children need protection from domestic violence even if the assessment concludes that the original referral for abuse or neglect is unsubstantiated

“…lead to a diversion of resources from the provision of support and services for actual cases of child abuse and neglect, into assessment and investigation”

This is essentially a repetition of the “swamping” argument of the first point, that children’s services will be overwhelmed by a surge of trivial reports.

“…result in poorer quality reports as there might be a perverse incentive for all those who may be covered by the duty (from police officers to school caterers) to pass the buck. This might mean the children are less protected than in the current system;”

In saying that mandatory reporting might encourage people to “pass the buck”, it appears to be saying that people will be encouraged to report suspicions rather than attempting to handle the problem directly. But this is exactly what we want people to do, and so does the Government[6]. We want child protection concerns to be brought to the attention of those with the training and authority to properly investigate. Quite how this could mean that “children are less protected than in the current system” is left unexplained.

According to recent research for the Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England, approximately seven out of eight abused children do not come to the attention of children’s services. Therefore our current problem is that we have far too few reports of suspected abuse and we need many more. In all too many recent cases, when abuse was discovered, it was subsequently found that the evidence was there and went unreported for some considerable time. Recent examples include

- Nigel Leat, who sexually abused children at Hillside First School for most of the 14 years he taught there. Behaviour of concern was noticed by other staff on 30 occasions. Reports were made to the head teacher eleven times, none reached children’s services. Leat was eventually caught when a girl told her mother who called the police directly without involving the school.

- Daniel Pelka, who was killed by his mother and her partner. Daniel attended school during the last six months of his life. During that time, staff noticed that he was emaciated and seriously underweight, that he was constantly hungry and trying to steal food from other children’s lunchboxes, and that he had unexplained bruises including what appeared to be strangulation marks on his neck. The school’s safeguarding arrangements were described as “dysfunctional” in the subsequent serious case review, a word that is rather kind given that they should more properly have been described as “nonexistent”.

- Jimmy Savile, who abused in just about every institution that he came into contact with. Most notable perhaps is the fact that nurses at Stoke Mandeville hospital, feeling unable to report their concerns about him, would tell patients to pretend to be asleep when Savile visited so that he would take no notice of them.

- Jeremy Forrest, a teacher at Bishop Bell Academy in Eastbourne, who formed a relationship with a 15 year old pupil and fled to France with her. Evidence of the relationship was known to staff for some time but not reported to children’s services.

Given present circumstances, anything that increases people’s willingness to report concerns should be welcomed.

“…focus professionals’ attention on reporting rather than on improving the quality of interventions wherever they are needed. This might encourage behaviour where reporting is driven by the process rather than focusing on the needs of the child;”

Before we had “practitioners”, now we have “professionals”. Let’s make a few appropriate distinctions here in order to avoid everyone becoming as hopelessly confused as the author of the consultation appears to be.

We don’t want teachers, nurses etc investigating abuse[7]. It’s not their job and they aren’t trained for it. Their unguided attempts at intervention are likely to be ineffective or possibly even actively harmful. We have quite enough cases now where schools or other institutions believe that they can effectively protect children (and also the institution’s own reputation) by dealing with abuse “in house”. However they end up protecting the abuser more than anybody else.

Instead we want these people passing concerns to children’s services who are trained to investigate and intervene. Therefore appropriate reporting can both be process driven and focus on the needs of the child, since an abused child needs to come to the attention of children’s services who are best placed to make an effective intervention.

Moreover, early reporting to children’s services will reduce the harm done to a child either by directly triggering an intervention, or less directly by providing children’s services with a pattern of behaviour on which they can eventually act. In either case, intervention can occur sooner than it otherwise might, both reducing the harm to the abused child and also preventing abuse of other children by earlier identification of the abuser.

This is all so obvious that to phrase this as a negative suggests that the consultation author is scraping the barrel for disobliging things to say about mandatory reporting.

“…lead to those bound by the duty feeling less able to discuss cases openly for fear of sanctions, hinder recruitment and lead to experienced, capable staff leaving their positions”

This happens now, but to those who wish to report but fear to for a variety of reasons. Quite why a reporting duty could lead to those to whom the duty applies becoming less willing to discuss cases openly is not explained. It is merely asserted as if it were self-evident fact. There is no evidence from the world’s MR countries (the majority of nations in the world) that supports this claim.

“…dissuade children from disclosing incidents for fear of being forced into hostile legal proceedings”

Few children disclose even now. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Australia has suggested that (for those who do eventually disclose) it takes an average of 22 years to disclose child sexual abuse to the authorities. No evidence is provided by the consultation author to explain why children may be less willing to disclose if mandatory reporting were to exist, and no evidence is given to the effect that children are sufficiently sophisticated to even think about “hostile legal proceedings”. If we believe that legal proceedings are hostile to children, then we should change them so that they become more child friendly. We don’t instead make it even harder for crimes against children to be prosecuted. The Royal Commission is about to release a paper on this subject.

Overall, children tell somebody about abuse because they want to be protected from it. They want something done so the abuse will stop. Because so few children disclose, every disclosure is immensely valuable and must get into the hands of those who can intervene effectively.

“…undermine confidentiality for those contemplating disclosure of abuse. Victims may be more reluctant to make disclosures if they know that it will result in a record of their contact being made”

This is a repetition of the previous argument. Moreover, since very few children disclose, even if this concern were valid then any effect would be marginal. Far more important to the effectiveness of mandatory reporting is that other signs of abuse are reported, those noticed by adults who have personal responsibility for children as defined in our draft legislation in Part 1.

“…have limited impact on further raising awareness of child abuse and neglect given the new Government communications activity, the existing high level of media scrutiny and the work of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.”

Awareness has increased. We now need to turn that awareness into action so that reasonable suspicions actually get reported and acted on. Mandatory reporting is primarily about stimulating appropriate action. This is the missing link in the present arrangements. Far too few children who are at risk of abuse or who are being abused are coming to the attention of the Local Authority. Media scrutiny will not of itself cure the fears of those who ask themselves “What if I’m wrong?” on seeing indications of abuse. The IICSA is going to be in session for years to come and may yet conclude that our awareness needs to be raised much higher than it is even after the recent high profile cases.

Paragraph 51 makes comparisons between referral rates in England and some jurisdictions which have mandatory reporting. The figures are worthless because, as Professor Mathews has stated the rates can be “markedly affected by such things as policy variations in setting evidentiary thresholds, the capacity of agencies to investigate, and whether there is an emphasis on evaluating existing harm or assessing the risk of future harm”. If you want a valid comparison between systems with and without mandatory reporting, you need to have a like-for-like comparison. You need cases counted the same way and for the laws and other arrangements to be otherwise similar except in respect of the presence or absence of the mandatory reporting duty. Furthermore the paucity of child abuse data gathered from Regulated Activities in England is astonishing.

The figures quoted in paragraph 51 have been used to misleadingly suggest that mandatory reporting would not in fact result in much of an increase in referrals at all, and that mandatory reporting is therefore a useless measure. But for this argument to be true, the other arguments offered against mandatory reporting, such as the swamping argument, must be false. LA children’s services could hardly be swamped by a measure that makes no change in the number of referrals.

For two mutually conflicting arguments to be made against mandatory reporting suggests that the consultation author has no significant evidence in favour of either argument, and/or that he is sufficiently against mandatory reporting for reasons unaffected by evidence that he is prepared to throw even mutually conflicting arguments at the issue in the hope that nobody will notice. Well, it didn’t work. We noticed.

Fortunately we have a like-for-like comparison available to us in Professor Mathews’ study.. Curiously it is not included in the annexes to the consultation documents. There is an underlying assumption in the consultation description of mandatory reporting that the reporter’s duty ends when the report is made. This is not so, or at least it need not be so. Once children’s services investigate, there may be a need for a child protection plan or other measures which will require attention by schools or other institutions which care for the child. Mandatory reporting should not affect these arrangements. The wording of the proposal implies that these existing arrangements would get abolished or at least ignored as a result of mandatory reporting. The suggestion is of a false dichotomy of a choice between mandatory reporting and other measures, whereas mandatory reporting should be implemented in concert with other measures designed to make the best possible use of the reports generated.