That is the essence of today’s statement by Home Secretary Suella Braverman giving the Government’s response to the final report of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sex Abuse. The report was seven years in the making. On the day it was published, the then Home Secretary Grant Shapps promised that “the government will respond in full to the inquiry’s report within six months”. The government missed that deadline by just over a month, and Shapps’ predecessor and successor Suella Braverman perhaps didn’t feel all that inclined to honour a promise made by someone who was Home Secretary for six whole days.

In Parliament, Braverman said of the report:

“It is a call for fundamental change, cultural change, societal change, professional and institutional change. I am pleased today that this government has risen to the inquiry’s challenge. We are accepting the need to act on 19 out of the inquiry’s 20 final recommendations.”

It’s rather noticeable that “government change” is not listed among the changes she outlined the need for. We noted also that she has “accepted the need to act” but hasn’t offered any specific actions will be taken in response to that need. Braverman went on to say that the statement “does not represent the government’s final word on the Inquiry’s findings”. It’s a relief given how threadbare the statement was.

On mandatory reporting, Braverman referred to a previous announcement accepting the need for its introduction. But no proposal for introducing it was made. Instead, the government is :

“launching a call for evidence which will inform how this new duty can best be designed to prevent the continued abuse of children and ensure that they get help as soon as possible”.

But the Inquiry report referred to ample evidence on the need for and structure of mandatory reporting. It might be an innovation in Britain, but plenty of other countries have it and there is already a Private Members Bill before Parliament which synthesises the best of overseas precedent and practice. If the government was serious about getting on with introducing mandatory reporting, it could and should simply have adopted the bill and ensured it was given parliamentary time. But nothing of the kind was proposed. It’s all a bit Groucho Marx “Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them…well, I have others.” It seems that the government doesn’t like the evidence in the IICSA report, so it is looking for other evidence that would justify a different approach.

Mandate Now has already described shortcomings in the IICSA proposal for mandatory reporting. It would be good to believe that the government shared those concerns, and that this is the reason for the new consultation. Unfortunately, the government’s determined inaction on the subject gives no reason for confidence. The consultation very much looks as if it is intended to provide an excuse for the government to do less rather than more, to implement something which can be called “mandatory reporting” but which lacks the essential features to make it effective.

Ahead of the statement, it was trailed that the big-ticket item would be setting up a redress scheme for victims. Acceptance of the need for a redress scheme was described as “a landmark commitment”. But no scheme was announced. Instead Braverman said that:

“we will carefully consult with victims and survivors, draw on lessons from other jurisdictions and we will make sure we honour the inquiry’s legacy as we design this scheme.”

Braverman stated that 19 of the 20 recommendations were being accepted “in principle” with details yet to be worked out about how (or even whether) they will be implemented in practice. It’s clear that the government has got almost nowhere with working out how to ‘deliver’, either in part or in whole, any of the Inquiry recommendations.

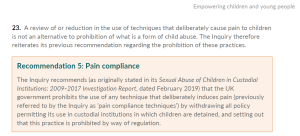

Braverman was remarkably coy about which recommendation is being rejected, she didn’t answer a direct question on the subject. On further examination it appears she has rejected Recommendation #5 – the withdrawal of the policy that permits ‘pain compliance’ techniques to be used in custodial institutions. These settings, which include Young Offenders Institutions and Secure Training Centres and Schools , are the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice. 1

- In England and Wales, children aged between 10 and 17 can be held criminally responsible for their actions. In February 2022, there were 414 children in custody. Once children are sentenced to custody, the Youth Custody Service (YCS) determines where to place them in the secure custodial estate based on each child’s individual needs, the youth offending team’s placement recommendation, and the accommodation available.