IICSA has failed

It must now be acknowledged that the Independent Inquiry into Child Sex Abuse (IICSA) has been a failure.

It ran for seven years, cost £180 million and produced nineteen investigation reports and twenty-five research reports totalling about 6,000 pages. The final report was 468 pages and contained twenty recommendations for government to act on. Much of it was extremely grim reading, describing unimaginable suffering endured by far too many children.

But, as of the present date, exactly three years since the IICSA final report was issued, the sum total of the IICSA recommendations implemented is … precisely zero.

How have we reached this sorry situation?

It didn’t help that between the commissioning of the inquiry and its final report, we had three changes of Prime Minister, and we have had a further two changes of Prime Minister since the report was issued. Governments often don’t feel bound by the promises of their predecessors to act on the recommendations of inquiries. That might be felt a bit unlucky, but the fact is that the average Prime Minister lasts about four years in office and the inquiry ran for seven years before producing its recommendations. So the inquiry just took too long. Several of the recommendations were blindingly obvious and could have been included in interim reports issued along the way.

It also didn’t help that the inquiry came at a time of acute political instability when politicians (at least in their own minds) had more important things to think about.

But the inquiry made things worse for itself in other ways. On the day the report was published, inquiry chair Professor Alexis Jay identified three recommendations as being of critical importance. They were the appointment of a cabinet-level Minister for Children, the setting up of Child Protection Authorities for England and Wales, and Mandatory Reporting of child sex abuse.

The Minister for Children recommendation was essentially useless. The recommendation did not state what responsibilities the new Minister should take, or how these responsibilities and the civil servants fulfilling them would be transferred from other departments. Without a clear template for the transfer of responsibilities, and a clear description of what benefits would occur as a result, there’s very little reason for government to attempt to implement this.

The Child Protection Authorities (CPA) recommendation was similarly confused and incomplete. The aim was for the CPAs to improve practice in child protection, provide advice and make recommendations to government in relation to child protection policy and reform to improve child protection, and inspect institutions and settings as it considers necessary and proportionate. It was also expected that they would also “monitor the implementation of the Inquiry’s recommendations”. But they haven’t been set up. What happened?

As the report said “Responsibility for monitoring and implementing institutional child protection lies with several statutory agencies and services, sector-specific inspectorates and government departments.” But again the report was not specific on how these responsibilities would be transferred into the new body. The report stated that the current inspection framework “fails to provide an adequate model for the external scrutiny of child protection in institutions”, and explained why.

But the IICSA proposal was for this new body to carry out inspections in parallel with existing inspectorates, giving rise to the quite obvious risk that a setting would be inspected by two different bodies against conflicting sets of requirements and genuinely be unable to fulfil both sets of requirements at once.

Worse still, the report stated that “it is not intended that the CPAs will have powers to regulate an institution by, for example, imposing a sanction for failure to implement improvements … The public exposure of failings in any report is envisaged to be sufficient to bring about the necessary changes.” That is just unbelievably naïve to anyone with experience of institutions dragging their feet over safeguarding changes.

If the existing inspectorates are not up to the job, then the recommendation should have been for them to be replaced with a specialist inspectorate with statutory powers to require changes and to impose sanctions on individuals and institutions who do not meet their requirements. But this was not proposed.

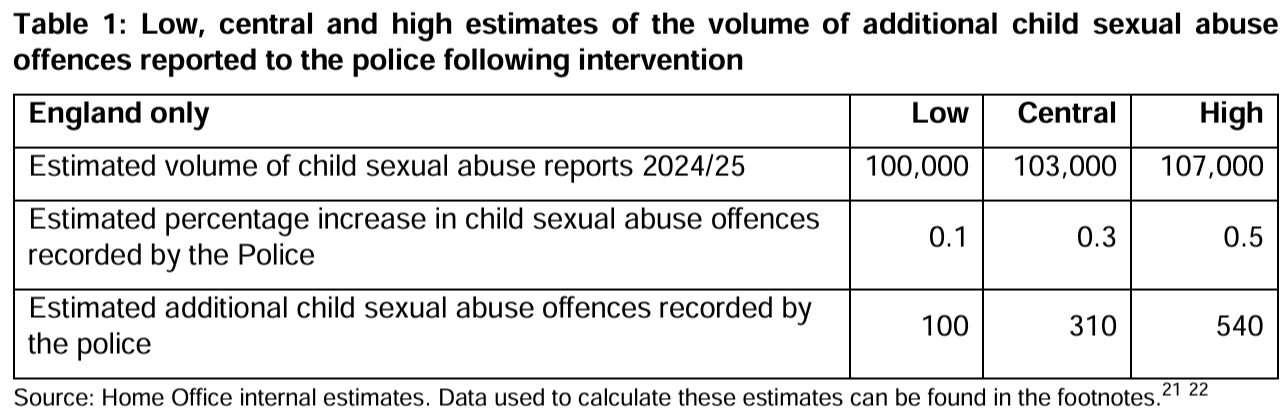

Mandatory Reporting should have been the easiest of the three recommendations to make and the hardest for government to wriggle out of. We already have laws implementing mandatory reporting of suspicions of bribery, money laundering, and financial activity related to terrorism. About 80% of jurisdictions worldwide have mandatory reporting laws relating to child sex abuse. There are plenty of models to choose from, and clear evidence that well-designed mandatory reporting is highly effective in combatting child sex abuse.

But again the IICSA report was confused. It spent several paragraphs describing the need for mandatory reporting, specifically of suspected abuse as well as disclosures by children (because disclosures either by perpetrators or children are relatively rare), and made it clear that nothing less than a criminal sanction for non-reporting of suspected abuse would change people’s behaviour.

But then the report completely undermined its own reasoning by saying “identifying indicators of abuse is more complicated than witnessing or receiving a disclosure of child sexual abuse and so a failure in respect of this aspect of the duty should not attract a criminal sanction”, and gave no further explanation why it had reached this conclusion. As a result, IICSA proposed a model of mandatory reporting that nobody else in the entire world uses.

The inquiry should have stood by its reasoning and recommended mandatory reporting for reasonably grounded suspicions of abuse, just as we already have for bribery and money laundering in the Proceeds of Crime Act 2003. Furthermore, the inquiry was absolutely full of experienced lawyers, so they should easily have been able to come up with some draft legislative wording that would implement what they wanted, and would have given government no option to water down the requirement.

But watering down is what has happened. The Crime and Policing Bill currently going through Parliament includes a “duty to report” disclosures (but not other suspicions) of child sex abuse but with no criminal sanction for non-reporting. Instead it is hoped that persons unstated will refer non-reporters to the Disclosure and Barring Service. But nobody has to do that either. There is a criminal offence of “preventing or deterring” someone from making a required report, but the description of the offence is such that it is permissible to persuade a person to delay making a report, without limit of time. It’s going to have no effect on the prevalence of abuse.

Finally, the inquiry provided no means by which governments could be monitored on their performance against the recommendations. It issued its report and then shut up shop. In doing so, it has demonstrated with startling clarity that it is not enough to try and shame people into doing the right thing merely by a one-off dose of adverse publicity. More tangible forms of pressure are needed.

But that lesson was not learned either in its recommendations nor in how the inquiry wound itself up. It has comprehensively failed.