The Law In Sport article was published on 30th July 2020. Mandate Now was sent a link by a social media follower who correctly thought it would interest us. It’s author Richard Bush is an Associate in Bird & Bird’s Sports Group, We have interpolated our comments into his article below using this ‘comment’ format in italics. All photographs and sound files form part of our commentary.

It is essential to any child protection and safeguarding system that concerns about the safety of those the system is designed to protect are reported to those who can take appropriate action. If that does not happen, the system is fundamentally undermined. Safeguarding reviews in sport,[1] and numerous cases outside of sport,[2] have consistently shown that failures in respect of the reporting of concerns have gone on to have serious consequences.

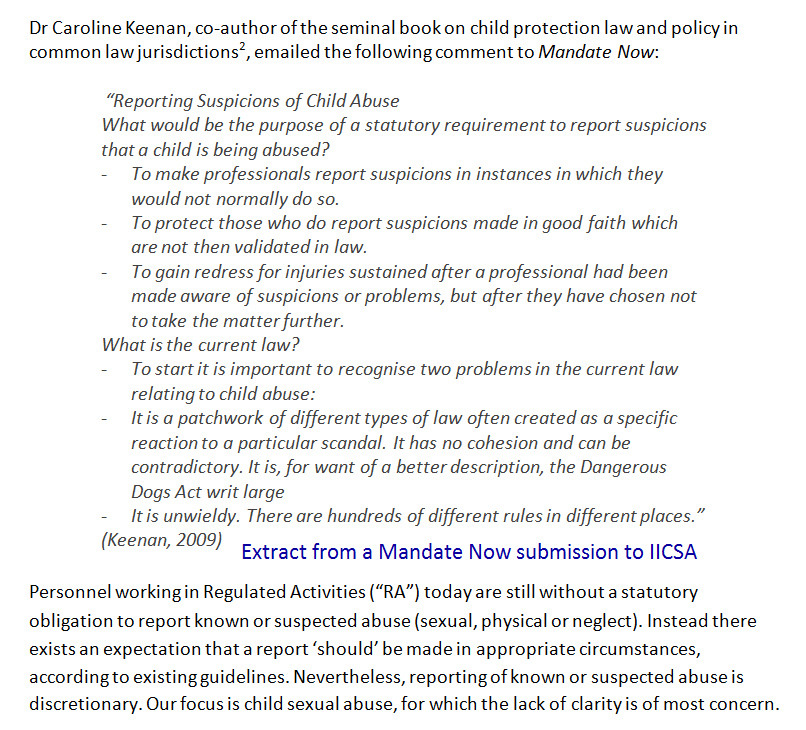

In England, Wales and Scotland, any member of staff working in a ‘Regulated Activity’ (institutional setting) such as sport who reports a safeguarding concern does so on a ‘discretionary’ basis. As a result, they are defined as a ‘whistle-blower’ with all the negative connotations that are attached to that term. The only protection afforded to ‘whistle-blowers’ is the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 which has little value. Making a referral of known or suspected abuse, whilst it is expected of members of a profession which is a ‘Regulated Activity’ (“RA”) such as healthcare, education or faith, remains entirely discretionary. In contrast, jurisdictions with well-designed mandatory reporting have a legal obligation on specified personnel usually working in RA’s to report known and suspected abuse on reasonable grounds to specified authorities. The law provides the member of staff with legal immunity and protection. The graphic below is taken from one of our two submissions to the MR seminars hosted by the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (“IICSA”) in September 2018 and April 2019. The first three bullet points are vitally important considerations to the introduction of functioning safeguarding in these settings. They chime with many of the child abuse shortcomings that have belatedly come to light in UK sport. Dr Keenan’s comments about the ‘current law’ are chillingly accurate. SGB/NGB’s seem unaware of its abysmal condition that so obstructs these organisations from delivering functioning safeguarding.

Child abuse is a crime in every jurisdiction yet in England, Wales and Scotland there’s no law requiring it to be referred to the statutory authorities (police or Local Authority), the latter for independent assessment. (most referrals are about suspected abuse)

The principal aims of a sports governing body (SGB) in respect of child protection and safeguarding typically include, in general terms:

- raising awareness of child protection and safeguarding issues, and creating a safe and secure environment for participation;

- ensuring that there are clear reporting procedures in place in order to (a) receive reports of abuse (which is the primary concern of this article), and (b) refer reports of harm/abuse to the appropriate external agencies and/or the police;

- ensuring that appropriate procedures are in place in order to respond to instances of harm/abuse, or potential harm/abuse and, where necessary, remove those who pose a known risk of harm from participation in the sport; and

- monitoring and maintaining appropriate policies and procedures in order to ensure that child protection and safeguarding standards remain at an appropriate level.

Absent of law, the bullet points in the article are a triumph of hope over reality. It’s an example of willing the end while SGB’s/NGB’s and their member clubs are given no ‘statutory’ means to deliver functioning safeguarding on which reliance can be placed. In fact the current framework hampers the delivery of effective safeguarding in these complex and strategically important settings. To the extent it works at all, it does so thanks to good people trying their best against the odds. Dr Keenan’s remark that the framework is ‘the dangerous dogs act writ large’ is elegant compared to our assertion that it’s a ‘bag of bits.’

The receipt of reports of child protection and safeguarding concerns by an SGB is especially crucial; because of course it is only if an SGB is made aware of concerns that it can meet these key aims, particularly:

- referring concerns to appropriate external agencies and/or the police (in the UK, a report to a local authority will in general terms be appropriate if it is suspected that a child or adult at risk is being abused or neglected, whereas if a child or adult at risk is in immediate danger the police should be contacted); and

- responding effectively to concerns within the sport itself (for example, by supporting affected individuals, addressing inappropriate conduct so that it is not repeated and, as above, removing individuals from the sport where that is necessary).

Therefore, every SGB should seek to create and maintain a strong safeguarding culture that encourages the reporting of child protection and safeguarding concerns. A possible step further would be to make the reporting of such concerns a duty, by making it a disciplinary offence for a participant to fail to report child protection and safeguarding concerns to the SGB.

It is only when a referral is received by Local Authority MASH or the police that the referring adult can have some assurance that it might be managed as suggested by the ‘guidance.’ In most mandatory reporting jurisdictions, referrals are made directly by the member of staff to specified statutory authorities. The more links introduced to a safeguarding referral, for example referring internally within the sports club, then to the NGB, the greater the opportunity for it to not reach the authorities which have the necessary powers to address the issues. The reason for referring internally first, in other words to the very body in which abuse could have been perpetrated, needs to be evidenced by those who promote this idea. The sound file below is an example of how it goes wrong and IICSA has heard similar evidence from a stream of witnesses throughout the hearings.

This article examines the mandatory reporting of child protection and safeguarding concerns in sport, and looks specifically at:

- the pros and cons;

- the main issue for SGBs to consider, including

- to which individuals should the proposed duty attach?

- what behaviour should be subject of a duty to report?

- which individuals should be protected by the proposed duty?

- whose behaviour should be subject of a duty to report?

- what level of knowledge of abuse would trigger the proposed reporting duty?

While this article is written predominantly from a UK perspective, it is hoped that its content will also be useful and informative from a wider international perspective (including for international federations as well as national SGBs).

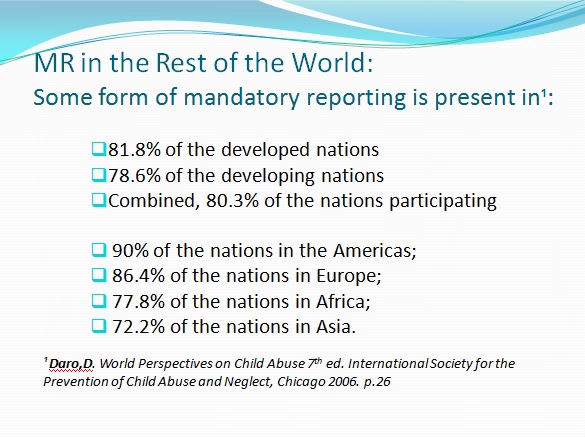

By not having some form of mandatory reporting, the UK (England, Wales and Scotland) is out of step with the majority of jurisdictions in the rest of the world .

Academics in MR jurisdictions find the safeguarding approach to RA’s by successive UK governments quite inexplicable. The reasons for this have nothing to do with the protection of children. The suggestion in the article that overseas SGB/NGB’s might have anything to learn from our framework, other than how not to do it, is curious. In the dog days of summer a few years ago a colleague ventured the suggestion that if government had designed a safeguarding framework specifically designed to fail – they couldn’t have done a better job than what we have.

Mandatory reporting – the pros and cons

Mandatory reporting already has an established place in the sports regulator’s arsenal when seeking to combat conduct that is seriously harmful to sport. In particular, in the context of anti-corruption, mandatory reporting provisions are commonplace, with most anti-corruption rules making it an offence for a participant to fail to report any corrupt approach made to him/her, or (to his/her knowledge) to another participant.[3] Mandatory reporting provisions do exist in the rulebooks of some SGBs in respect of child protection and safeguarding, although they are not as common.[4]

The same broad logic behind making a failure to report a disciplinary offence applies in both the anti-corruption and child protection/safeguarding context. In particular:

- participants should want to report matters that cause serious damage to the sport (and, particularly in the child protection/safeguarding context, damage to the health and wellbeing of others);

- reporting helps ensure that serious misconduct does not go unchecked (reports can be passed on as appropriate and addressed within the sport); and

- reporting can help ensure that others are not seen as somehow complicit in serious misconduct (by failing to report it).

So far the article has been discussing MR authored by the “RA” (SGB/NGB) and policed by it with a “professional sanction” potentially applied by the SGB/NGB ‘should‘ failure to report be discovered – usually years later. This is little more than ‘pretend’ MR.

Such an ad hoc arrangement would provide none of the vital components statutory legislation delivers to this safety critical function and therefore could have no reliance placed upon it. The article has also not made clear that a reporter in these circumstances would remain a whistleblower with all the paralysing shortcomings this delivers to reporting a ‘suspicion.’ (example in sound file above). It’s counterfeit MR or to put it another way – the status quo in new clothes.

Put concisely, it is possible to identify the following potential benefits for an SGB in introducing mandatory reporting in the child protection/safeguarding context:[5]

- increased awareness of the importance of reporting child protection and safeguarding concerns, both by those placed under a duty to report and other stakeholders;

- identifying more child protection and safeguarding cases, potentially at an earlier stage in the life of such cases; and

- creating a higher risk environment for abusers or potential abusers.

We are unfamiliar with any SGB/NGB or equivalent RA grouping that has introduced a ‘form’ of MR. The Church of England claimed it had in a radio interview which prompted us to write to Peter Hancock, Lead Bishop for safeguarding at the time – See the correspondence here. Applying a counterfeit MR label to anything that has the word ‘safeguarding’ on it is happening repeatedly, and by some very surprising organisations.

It’s worth repeating that all professional RA’s (education, healthcare, faith) have is an ‘expectation’ to report known or suspected abuse and a potential sanction if it is subsequently discovered that a report was not made contemporaneously. It’s stable-door country and the inquiry sees and hears the failures from this abysmal arrangement week in week out from witnesses.

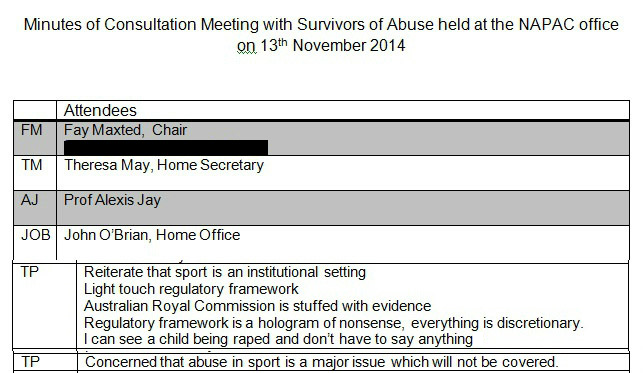

A representative from Mandate Now was invited to a meeting in Nov 2014 on the future of the Child Abuse Inquiry following the resignation of the second chair Fiona Woolf. We lobbied for sport to be included into what became IICSA which was belatedly given statutory status. Our request was ignored.

However, it is also possible to identify the following potentially problematic issues for an SGB in introducing mandatory reporting – again, put concisely:

- an increased number of unsubstantiated referrals and/or poorer quality reports (as a result of those under a duty to report over-reporting or “passing the buck”), making it harder to distinguish serious cases, and diverting the SGB’s finite resources from support for such serious cases into the assessment and investigation of other cases;

- the possibility of dissuading children, adults at risk and others from disclosing incidents to individuals under a duty to report for fear of their confidentiality being undermined and/or being forced into the investigative process and any consequent disciplinary/legal proceedings when they do not wish to be; and

- the possibility of retraumatising those who have suffered harm/abuse and discouraging those abusers who might wish to seek help in respect of their conduct from those within the sport.

These three bullet points are from the buffet of disinformation provided by among others the Department for Education.

From anywhere in the world, where is the evidence of Regulated Activity initiated non-statutory MR (MR of what, applied to whom and reporting to where?) producing increased ‘unsubstantiated’ reports? It simply does not exist.

Where is the evidence to support the claim MR dissuades children from ‘coming forward?’ This ‘coming forward’ narrative is really very tiresome particularly when adults in RA’s all too frequently fail to refer known and suspected abuse to the statutory authorities. Unfortunately the article ignores this vitally important point.

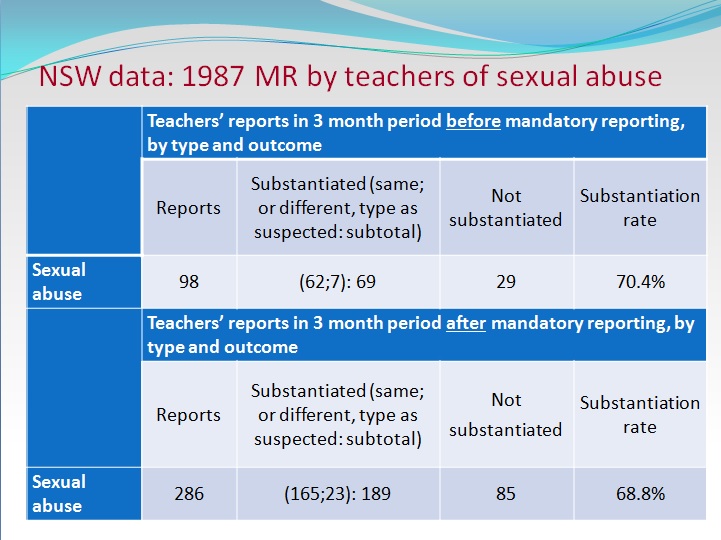

Here is data from 1987 when New South Wales extended MR to education in that State.

The difference is significant and note the substantiation rate is within tolerance contrary to the suggestion in the article.

On the final ‘retraumatising’ point we would welcome seeing the evidence on which this comment is grounded.

Unfortunately, there is no academic consensus concerning the efficacy of mandatory reporting in the child protection/safeguarding context generally[6] – meaning it is not possible to offer any general recommendation as to whether or not a mandatory reporting provision should be introduced by SGBs as a matter of course (the author is not aware of any academic research into mandatory reporting specifically in the context of sport).

Mandatory Reporting is a statutory instrument, not an option for an SGB to decide upon. An in house MR scheme is a non-starter for the reasons previously given.

To illustrate – subject to the important caveat that the context of sports regulation should perhaps not be considered as on all fours with the criminal law in this area – reference can be made to the effect of mandatory reporting laws in Australia, where all states and territories have mandatory reporting laws (although, perhaps reflecting the questions considered below, the laws differ significantly in their detail).[7] In Western Australia, following the introduction of mandatory reporting in respect of child sexual abuse, the number of reports increased by a factor of 3.7, with the number of substantiated reports doubling. In Victoria too, a study found that there was an initial increase in reports for the first two years following the introduction of the law, although the number of reports then stabilised.

WA was the last State to introduce MR, its leadership was set against it and in 2009 when it was belatedly introduced, it was poorly designed, and launch was not well-managed. Police were included into MR and there was a potential prison sentence for failing to report. Data reveals police in particular over-reported children at risk in domestic abuse cases for fear of the heavy sanction of imprisonment. Children’s services were unprepared for this increase. Having amended this aspect, referrals and substantiations returned to expected norms. The article below is about the introduction of MR to WA and takes data from four years before its introduction and three years afterwards.

To aid those who may not have access to the article we reviewed it here and have been reliably informed it presents an accurate picture.

At face value, the statistics from Australia strongly support the introduction of mandatory reporting, and an academic who presented to the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse accordingly concluded (among other things) that “[e]mpirical evidence and ethical considerations strongly support [the] introduction of mandatory reporting for child sexual abuse”.[8] However, another academic, who presented to an NSPCC roundtable (and also considered research relating to Australia), noted particular concern that the increased number of reports places far too much focus on investigation at the expense of wider child protection and safeguarding services, concluding that there is “overwhelming evidence that mandatory reporting systems are in chaos worldwide” and that there is “NO empirical evidence linking mandatory reporting with reduction of … child maltreatment”.[9]

The NSPCC Roundtable was held in 2014 and for the record Mandate Now was not invited. Indeed, no one with a deep appreciation of MR was invited to the gathering. Furthermore Professor Hoyano’s presentation to the roundtable (see pages 20 to 28) relied on two particular matters – research by Harries and Clare and ‘substantiations.’

Harries and Claire can be addressed very quickly thanks to an article on our website from 23.11.15 entitled : No Reliance can be Placed on a Report Used by Academics and others to Dismiss Mandatory Reporting – here’s why Please note that the 158 participants in the Harries and Claire research were strongly supportive of MR for sexual abuse yet this seems to be ignored by the authors of the paper and those who cite Harries and Clare to justify opposition to MR.

Substantiations are repeatedly misused by those against MR.

Substantiations are not a measure of success. In jurisdictions that have MR for child sex abuse, only child sexual abuse can be substantiated – nothing else. If the same child is referred by more than one mandated reporter, there can only be one substantiation. In all jurisdictions children who are in unsubstantiated referrals receive greater support services than substantiated referrals. MR encourages prompt intervention often avoiding abuse of the child and therefore once again no substantiation can occur. Nonetheless, such children often require significant support from children’s services. Important articles exist on the subject of substantiations which explain the shortcomings of the term.

Issues to consider in respect of introducing mandatory reporting

We are commenting at the top of this paragraph to re-emphasise that Mandatory Reporting is a statutory tool rather than a user group initiative. When law is enacted it applies to specified Regulated Activities including sport one hopes which conforms to the definition of RA. An article on our website from April 2017 : #MR Bill Underway for USA Athletes following Senate Hearing and Grey-Thompson Now Wants It

When considering the introduction of mandatory reporting, an SGB will need to weigh up the broad pros and cons identified above, the answers to a number of specific questions (set out below), and the specific circumstances of the sport and the SGB itself (not least, the SGB will obviously need to consider whether or not it has adequate resource to respond to any increased volume of concerns).

Mandatory Reporting in most jurisdictions sees the mandated reporter report firstly to the statutory authorities and not the SGB/NGB which should never ‘investigate’ an incident.

But perhaps the first consideration is a matter of principle, which is whether an SGB is prepared to introduce a disciplinary offence that punishes omissions by participants rather than their active conduct. By way of analogy, the general English criminal law position is that a person cannot be held liable for not doing something, although there are a few exceptions to this where the circumstances justify it –

There are in fact several more examples of mandatory reporting in English law. The first is the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 – s.330 which mandates the reporting of suspected money laundering. There is also the law used in Northern Ireland to introduce mandatory reporting of known or suspected abuse in education in 2006 following the Cabin Hill School abuse inquiry. This used existing law Section 5(1) of the Criminal Law Act (1967) which was anti-terrorist legislation. In short the law said – it’s a crime not to report an indictable offence, which of course includes child abuse. At the time it produced an excellent safeguarding guidance grounded on application of this law to safeguarding – it was prescriptive and issued by the Department of Education Northern Ireland. When the conservative government took office it all changed and subsequent administrations diluted it out of existence.

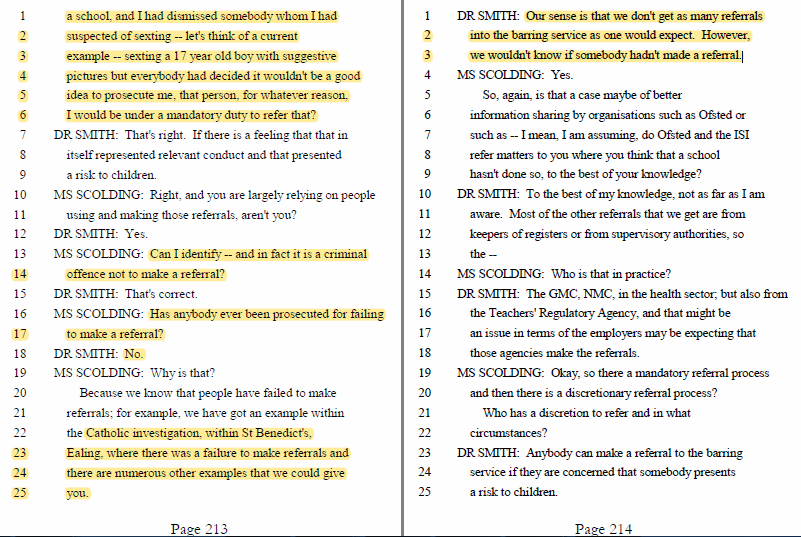

Another example of mandatory reporting exists within safeguarding in England and Wales although it too is not enforced. The law is s.38 (1)b and (2) of SVGA 2006 ‘Duty to provide information’ which is contained in the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups and importantly pertains to Regulated Activities making a mandatory referral to the Disclosure and Barring Service in prescribed circumstances. The law states that a person found guilty of failing to make a referral to the DBS is liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding level (5) i.e. £5000. However, this is not working. We wrote to Professor Jay the Chair of IICSA in advance of Dr Suzanne Smith, Director of Safeguarding DBS, giving evidence to the inquiry. In it we set out the shortcomings. Our letter is here, we used football as an example of the dysfunction. Below is an extract from the transcript of questions from counsel to Dr Smith and the answers she provided. They reveal the DBS can have no reliance placed upon it :

one example being a mandatory reporting law in respect of known instances of female genital mutilation (a form of child abuse).[10] However, insofar as an SGB might have any concerns in principle with introducing a “crime of omission”, it might feel that the importance of the child protection and safeguarding context – like the anti-corruption context in which such provisions relating to failures to report are commonplace – justifies it. And, in any event, an SGB’s concerns might in practice be mitigated by:

- being clear what it will do in response to the reports it receives, both in terms of dealing with a possibly increased volume of reports, and (as it should be anyway) in terms of how it treats individual reports;

- judicious enforcement of any mandatory reporting provisions; and

- the exact scope of the duty that is imposed.

A combination of empirical evidence and mandatory reporting legislation addresses most of these matters. We authored Amendment 43 for Baroness Walmsley (LibDem) which secured the long delayed ‘Reporting and Acting on Child Abuse and Neglect’ consultation. Of course we made a submission to the consultation which included draft legislation that varies from Amendment 43. It’s available in this link. The changes stem from practice information, data and research from common law jurisdictions.

There are a number of fundamental questions to consider in regard to the scope of the duty to be placed on participants. In general terms, the more concerns that will be caught, the more comfort an SGB might have that it is being made aware of concerns, but the main risk in adopting a broad approach is that there will be a higher number of unsubstantiated reports. Conversely, a narrower scope is likely to result in a fewer number of total reports, but those reports might be of a higher quality. Each of the questions set out below essentially requires addressing this balancing act.[11]

To comment in detail on the above assertions would take too long and it is in part covered in the earlier commentary on substantiations. Reading our submission to the consultation addresses all points.

1. To which individuals should the proposed duty attach?

A mandatory reporting duty that applies broadly obviously seeks to ensure that a great number of concerns are reported but, in practice, depending on the total number of participants an SGB has under its jurisdiction and/or its ability to publicise the duty, it might be difficult to ensure that all relevant participants are sufficiently aware of the duty to make it effective. A narrower application will mean that fewer concerns are caught, but the duty will perhaps be more pronounced for those who are subject to it, meaning it could be more effective.

While mandatory reporting outside of sport often casts a relatively wide net, one strong argument in favour of attaching a duty to at least those in leadership positions within sport is that it is they who have the ultimate decision-making capacity and it is they who will potentially be motivated (consciously or otherwise) not to report child protection/safeguarding concerns – if, for example, they are concerned about their reputation, the reputation of a person whose conduct should be reported, and/or the reputation of an organisation.

What is the definition of ‘leadership’? If it is the senior management only, then the point of MR is misunderstood. MR is designed to mandate a report in prescribed circumstances and to support and protect the reporter. If MR is applied only to the leadership of the organisation the dire unintended consequences would quickly become apparent.

See our evidenced submission to the government consultation to understand our position on this matter.

2. What behaviour should be subject of a duty to report?

Child protection and safeguarding concerns can range from serious cases of sexual, physical, and psychological abuse, and neglect, to less serious instances of ‘poor practice’ (e.g., an ill-judged remark or an isolated breach of a social media policy). Obviously, in an ideal world, there would not be any instances of even poor practice, but in reality it is very unlikely to be appropriate to treat a failure to report a low level instance of poor practice in the same way as it would be a serious instance of abuse.

The narrower the range of behaviour that is covered, the clearer the application of the duty is likely to be, e.g., if the reporting duty were to apply only to child sexual abuse, what constitutes (or potentially constitutes) child sexual abuse will to most people be relatively clear (particularly if there is a good level of awareness within the sport). However, while in many instances it will be possible to distinguish between cases of abuse on one hand, and poor practice on the other, there is perhaps less justification in differentiating between different types of abuse, e.g., treating sexual abuse differently from physical abuse, psychological abuse, and neglect.

In very general terms, a sensible and logical approach would be to ensure that any reporting duty mirrors the abusive conduct that is prohibited under the SGB’s child protection and safeguarding rules and regulations.

See our evidenced submission to the government consultation to understand our position on this matter.

3. Which individuals should be protected by the proposed duty?

At first glance, this might seem like a simple question, in that the obvious answer is that a mandatory reporting requirement should protect the same individuals who are protected by the SGB’s child protection and safeguarding rules and regulations – most commonly, children and adults at risk.

However, if an SGB has safeguarding (or similar) rules that seek to protect participants more generally, i.e., the protection afforded by the rules extends to adults who would not traditionally be considered as ‘at risk’, consideration might be given as to whether a mandatory reporting requirement should seek to protect all participants, or be limited to concerns relating to children and ‘adults at risk’ (i.e., those who have more traditionally been considered as vulnerable).

See our evidenced submission to the government consultation to understand our position on this matter.

4. Whose behaviour should be subject of a duty to report?

Again, this might seem like a simple question, in that the obvious answer is that abusive conduct by any participant in the sport should trigger the mandatory reporting duty. However, while that might well be appropriate, two specific considerations might be worth some reflection:

- If an SGB is particularly concerned by abuse being committed by certain individuals, for example by coaches or others in a ‘position of trust’, then it might be reasonable to limit the mandatory reporting requirement to abusive conduct committed by such individuals (in order to meet that specific concern).

- Whether or not the mandatory reporting duty should be triggered only by (a) the conduct of those who are participants within the sport, i.e., those under the jurisdiction of the SGB and against whom the SGB can take disciplinary action itself, or (b) the conduct of any individual, whether under the jurisdiction of the SGB or not, whose conduct has harmed, or risks harming, a participant within the sport. The latter approach is considerably broader but would enable an SGB to extend their ability to protect their participants (in particular by reporting such concerns to appropriate bodies, such as relevant external agencies and/or the police).

See our evidenced submission to the government consultation to understand our position on this matter.

5. What level of knowledge of abuse would trigger the proposed reporting duty?

The level of knowledge required to trigger the duty to report can be placed on a spectrum, ranging from ‘known abuse’ at the highest end, to ‘any suspicion’ at the lowest end, with ‘reasonable suspicion’ being somewhere in the middle. The risk at the higher end of the range is that a mandatory reporting duty is ineffective because few cases reach the necessary threshold (and, in terms of proving an offence of failing to report, it is harder to prove that the participant had the requisite level of knowledge) – but in cases where it does the need for the report should be more obvious. At the lower end of the range, more reports will be caught by the requirement, but there is a risk that many will prove to be unsubstantiated.

It’s for the reporter to report known or suspected abuse (on reasonable grounds) to the statutory authorities, not the SGB or even the ‘club officers’ to decide whether an incident reaches a threshold for it to be referred. See earlier comments about the number of links in the reporting chain.

Also : See our evidenced submission to the government consultation to understand our position on this matter.

Concluding remarks

The introduction of mandatory reporting in the context of safeguarding in sport is not by any means a straightforward matter. It might be appropriate for some SGBs, but not for others. One SGB might justifiably consider that it has instilled a sufficiently strong safeguarding culture such that child protection and safeguarding concerns are raised as a matter of course, and therefore a mandatory reporting duty is not necessary, or simply that the potential pros do not outweigh the potential cons. Another SGB might see a mandatory reporting duty as an essential step in most fully addressing child protection and safeguarding issues in its sport, or in a particular area of its sport. A further SGB might wish to introduce a mandatory reporting duty but consider that it does not have sufficient resource to do so effectively or without risking its existing processes.

The underlying suggestion that an SGB/NGB can itself introduce functioning MR is mistaken. Statutory legislation is needed for the reasons we have explained. No reliance could be placed on MR introduced by an SGB/NGB as most of the serious shortcomings that exist in the current ‘discretionary reporting’ model in England and Wales would be retained.

However, in all cases, the introduction of mandatory reporting is something that does warrant serious consideration, because (a) history has shown that failures in respect of reporting child protection and safeguarding concerns can have very serious consequences, and (b) a mandatory reporting duty can, where it is appropriate, serve to further the aims of SGBs’ child protection and safeguarding systems.

And, finally, whether mandatory reporting is introduced or not, SGBs should ensure that their reporting procedures are clear, well-publicised, and easily accessible, with appropriate support made available to those making reports, or those who wish to do so.